This article is specifically written for songwriters who may already have experience releasing their own music, writing for other artists (or are aspiring to do so), or already have a music publishing contract in front of them. What is a publisher? What do those confusing clauses really mean and how can publishers help you?

Music publishers in today’s modern context still play an important role in administering and promoting your music. However, it’s important to be able to understand the terms and conditions that come with working with a publisher. It is always in your best interest to understand what you’re signing – what you stand to gain, and what you’re signing away.

Here, you’ll find a very general guide for what to look for in a publishing agreement. In this article, we set out 5 particularly important areas an artist or composer should pay attention to, based on the writer’s personal experience as a musician who happens to be a lawyer as well as the experience of fellow musicians in the industry. This way, you can “cut your losses” so to speak and walk away (relatively) unharmed if something does go wrong.

Please note that this article is NOT comprehensive and we will not go through everything that could possibly be an issue. This article is also not intended to be a substitute for legal advice and you should look for a lawyer if you think there is a lot riding on your deal with the publisher.

What is a publishing agreement/ publisher?

A publishing agreement is an agreement you enter into with a publisher. Without going into too much detail, a publisher’s job is essentially to help with monetising the songs you write through various sources (often referred to as “exploiting” your songs – don’t be scared when you hear this). What the publisher does to exploit and monetise your work is a topic for another time.

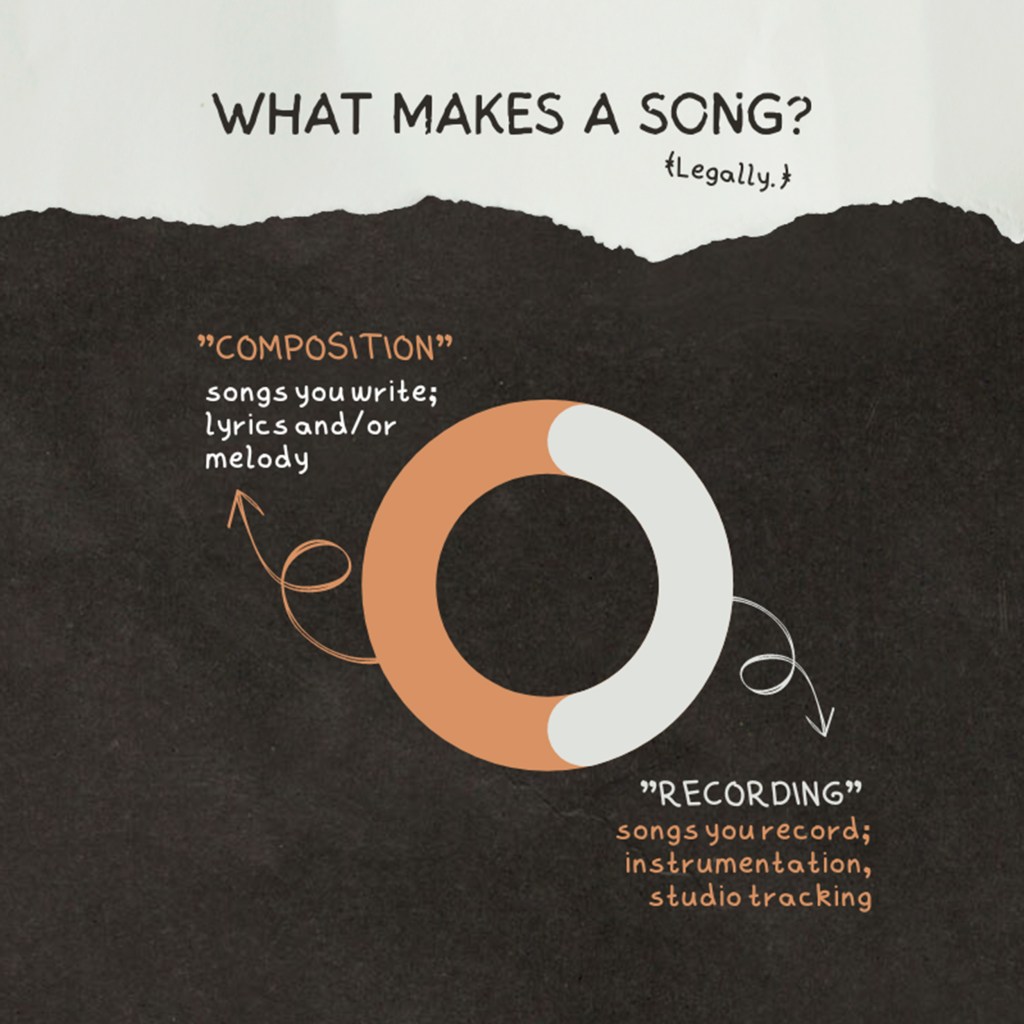

As a start, you should know that there is a distinction between songs you write (which we call “compositions” in this article) and songs you record (which we will call “recordings”). As a quick explanation, you will have rights in the songs you write (compositions), regardless of whether you perform or record them yourself, or if other people do. You will also have rights in sound recordings you record (recordings), regardless of whether you wrote the songs.

Publishing deals with the compositions you write and NOT the recordings you make. Recordings are dealt with under distribution or recording agreements. If you are an artist who writes your own songs, you can separately monetise both the composition and the recording.

Preliminary: Single song or term agreement?

The first thing you should check is whether your agreement is a “single song agreement” or a “term agreement”. A single song agreement, as the name suggests, means that you are only working with that publisher on that one song. This leaves you free to deal with other publishers for your other works.

A term agreement, in contrast, usually involves you working exclusively with the publisher for all your compositions for the duration of the “Term”, a concept further discussed below. Historically, a term agreement usually comes with an advance payment by the publisher to the composer. As this is not common practice (at least from the writer’s personal experience) in the local Singaporean scene, the concept of advances will not be covered in this article. It suffices to say that you should consider what the publisher can offer you for locking you in with them if they are not paying you upfront.

While the rest of this article is generally more relevant to term agreements than single song agreements, it is still useful to think about the following points.

Five points to consider

- How long are you stuck with them?

Publishing contracts will provide for the “Term” of the contract. This dictates how long your contract with the publisher lasts. This usually affects other important terms, such as how long you are “exclusive” with the publisher (meaning that you can’t write for others) and what compositions you are obliged to give to the publisher. From a rough survey, the “Term” usually ranges anywhere from one to three years.

Publishing contracts sometimes contain tricky language which has the effect of making the “Term” longer than it might seem at first glance. One area to be particularly conscious about is the concept of “option periods”. Option periods essentially grant the publisher the option to renew the “Term” for a set period of time without further agreement from you and whether you want to or not.

Quick math: Let’s say that the “Term” is three years and the publisher has three options to renew the “Term” for a further period of three years. This means that at the end of every three years, the publisher can extend the “Term” for an additional three years, three times. In this example, this effectively locks you in for 12 years should your publisher desire this.

This is particularly unfavourable because it means that (1) if you don’t like the publisher, but they still want to keep you locked in, they have the option to do so and (2) if the publisher doesn’t like you/your work, they can choose to drop you at the end of each option period.

Another area to watch for is whether the “Term” is automatically extended until the completion of some deliverable by you (usually called the “Minimum Delivery Commitment”). Depending on how “Minimum Delivery Commitment” is defined, it could cause the “Term” to be indefinite. This is further discussed below and expanded on in point 2.

For example, “Minimum Delivery Commitment” could be defined to be an unrealistically high number of compositions or require many conditions to be met before counting a composition towards the “Minimum Delivery Commitment”. This might cause you to be trapped in the publishing contract forever, especially when combined with the concept of “option periods” as discussed above.

- What do you have to deliver?

You should pay attention to what your delivery commitments are under the publishing contract.

The publishing agreement may ask for you to give ownership of specific compositions to the publisher. The specific compositions will usually be set out in a document called a “schedule” attached to the publishing agreement. The publisher may also ask you for all the compositions you write during the “Term” (discussed further below).

If the compositions in question have already been written, you should make sure that you are able to transfer such ownership. There may be issues if you co-wrote the composition with someone else and you should raise this with the publisher so that this can be managed.

As alluded to above, the concept of “Minimum Delivery Commitments” is an important one. A publishing agreement may require that you write a minimum number of compositions. This is not favourable to you, even less so if you’re a part-time artist/musician. Publishers generally want this to ensure that there is a pipeline so they have better bang for buck for promoting you. However, at least in this writer’s opinion, publishers are much less justified in asking for this if they aren’t paying you an advance.

Worse still, this sometimes gets combined with option periods (discussed above). The result is that you potentially have to deliver a minimum number of songs for every option period. This could end up being a lot of songs.

More quick math: Say the publisher has 3 options to renew your contract (with each option being three years long) and requires a minimum commitment of 10 songs for each option period. This means you could be on the hook for 30 more songs for 12 more years (not including the songs which you have to deliver for the initial period). This is a lot of songs for potentially a very long time.

You should think long and hard before agreeing to this. If you do, consider very carefully whether you can deliver all that you have promised to.

- What else are you giving away?

On top of the compositions you are obligated to deliver, as discussed in part 2 above, you should also pay attention to what else you are giving the publisher as a result of the publishing agreement. You should make sure that you are not giving away more than what is necessary for the publisher to do what it promised it would do for you. Here are some things that publishers may ask composers for which you should be wary about:

· The agreement may require that you work exclusively with the publisher during the “Term”.

· Related to the above, the agreement may require you to give the publisher ownership of all compositions you write during the “Term”. This has major implications as this means that anything you write during the “Term” will be owned by the publisher. As such, you may potentially be restricted from using what you write during the “Term” how you want to. This may potentially include compositions you write for corporate gigs (even if the publisher had nothing to do with getting you the gig) and potentially even what you write for fun or with a friend.

· Sometimes the publishing agreement may go even further and require you to transfer ownership of compositions prior to the “Term” as well. This presents an issue if you have previously either licensed or transferred rights in previous compositions to others (e.g. to a corporate who paid for songwriting services or another publisher).

It is debatable whether this is fair for the publisher to ask for the above if they are not paying you an advance.

One other issue is the type of content you are giving away. The publishing contract may ask for more than just musical works and may extend to literary or dramatic works. If you are a writer as well as a songwriter, this will be a problem as you will technically be giving the publisher not only your compositions but also any literary works you write (such as plays, poems or books). Music publishers typically do not have the ability to exploit anything other than musical works (i.e. compositions) and should not be including this in their contracts.

- What does the publisher have to do for you?

Agreements with publishers are usually pretty sparse on what the Publisher has to do for the Artist. It will likely be difficult to ask the Publisher for many obligations (unless you are a mega superstar). The publishing contract will usually grant the Publisher the right to decide how, and to what extent, to exploit the compositions you give them.

The contract may also provide for an obligation by the Publisher to use reasonable efforts in promoting you. Try to have this included in your publishing contract. This has two effects: (1) you at least get some express assurance that the publisher must at least do something for you (though not much) and (2) a failure by the publisher to do something for you could potentially be grounds to terminate the contract, though not a very reliable one.

If you can’t get the publisher to give this to you, it becomes all the more important, in our opinion, to ensure that:

(1) what you give the publisher is limited,

(2) the “Term” of the agreement is short and without option periods, and

(3) that you can get your compositions back after the agreement ends.

This brings us to our next point on termination.

- Can you get the rights in the compositions back after termination of the contract?

You should try to get back the rights in your composition after your contract with the publisher comes to an end. The contract may be phrased such that the Publisher gets to keep the rights in the compositions even after the contract terminates.

This is not good for you. Some issues that might arise are that:

· if you gave the publisher all compositions you wrote during the “Term” to the publisher, you won’t be able to otherwise exploit them (e.g. sell the composition) on your own, even after the publishing agreement ends

· a future publisher you want to work with might be less willing to work with you if a lot of your previous compositions are tied up with other publishers

Ensuring that you have the right to own your compositions again before signing the publishing agreement might save you a difficult conversation down the road.

Publishers will likely fight you on this point if you bring this up. The logic of the publisher is that they deserve to keep holding the rights in your compositions as they have already expended the effort to promote them. The counterargument is that (1) it may be unclear how much effort was actually expended by the publisher and (2) a future publisher’s effort in promoting future compositions may trickle down and benefit your current publisher, which may not be fair for the future publisher as well.

Here are some potential compromises you can consider:

· You might consider asking for the return of just the compositions which have not been exploited yet.

· You can ask to get your compositions back in a situation where the publisher is in breach of the publishing agreement; for example, if the publisher failed to use reasonable efforts to exploit the compositions.

· Agree to include a “sunset clause”. This allows the publisher to collect some money even after the compositions are returned for a set period of time. This helps balance some of the concerns the publisher has on already putting in effort to exploit the compositions.

· Alternatively, you can also try structuring to “buy out” the compositions from the publisher. However, note that these are more advanced concepts that likely require the assistance of a lawyer to help you draft.

· You can ask for the relevant compositions to be “exclusively licensed” to the publisher for a set period of time rather than “assigned”. Without getting into the technical bits, the difference is that you will usually get the rights in your compositions back after the set period of time is over if your compositions are licensed out while you usually don’t if they are assigned to the publisher. Publishers will likely fight you on this for, amongst other reasons, the reasons above. Additionally, the language on this may be tricky and you will likely require the assistance of a lawyer to help you with this.

Conclusion

This article wasn’t written to help you negotiate the deal of your dreams. There are still many important terms we did not discuss. For example, the topic of advances and the calculation of royalties are entirely different beasts to tackle and add further degrees of complexity.

However, it is intended to deal (very generally) with some terms to help you avoid a worst case scenario. It’s worth deeply considering the points above so you don’t meet with a nasty surprise years down the road.

As a reward for making it this far in what may have been a difficult read, we conclude with two broad tips:

- If the publisher tells you that something is in the contract because it is “standard” and claims that they won’t enforce it, it is not a good reason to leave it in the contract if you think the term is objectionable. Their “promise” not to do so may not hold up if things get ugly.

- If the contract requires you to do or promise something and you think it is objectionable, ask the publisher why they need it. If they can’t justify including it, you should seriously consider taking it out.

Special thanks to George Hwang of George Hwang LLC for his feedback. All errors and mistakes are the writer’s own.

About the author:

Jon is a musician and a lawyer.

As a practising lawyer, he has worked on matters relating to the media and music industry. He also works on a wide range of corporate and commercial transactions as part of his legal practice. In doing so, he has honed the technical skills that can only be picked up through the rigours of legal practice.

In addition to being the lead guitarist, Jon is also one of the operational driving forces behind Singaporean band Astronauts, producing original music.